Allow me to stray a bit from my self-assigned task of blogging about meat eating and, somewhat inspired by last few posts, to digress into my professional interests: water.

As an engineer primarily focused on the financial aspects of water service provision, I have developed some knowledge of what it takes - technically and financially - to bring water to your tap and to take sewerage back out again. This first post will address the technical aspects.

To put it briefly, the water part of the system is composed of the following:

Obviously, building, maintaining, and operating these infrastructures is very expensive, and they must be operational 24/7. This is both a matter of convenience and public health. In addition, empty water pipes are subject to infiltration from ground pollutants (see above), and you should never drink tap water in a city where supply is not available on a 24/7 basis. Costs are directly linked to the quality of intake water, the required capacity of infrastructure, the required quality of drinking water (up to or beyond WHO guidelines), the terrain, and the required quality of treated effluent.

In principle, the burden for recovering the cost of investment, maintenance, and operations should be born by consumers, according to how much they consume and how much they pollute (industries pollute water more than toilets, usually). In practice, costs can greatly exceed the population's ability to pay and regulations around the world vary greatly so that this rule is not always applied.

Next post: how much you should pay for water.

As an engineer primarily focused on the financial aspects of water service provision, I have developed some knowledge of what it takes - technically and financially - to bring water to your tap and to take sewerage back out again. This first post will address the technical aspects.

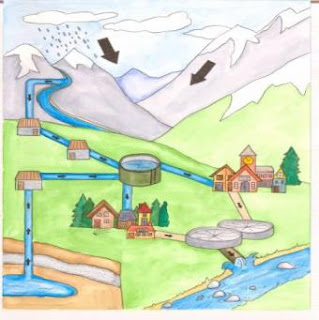

To put it briefly, the water part of the system is composed of the following:

- an intake, where raw water is taken from the environment : wells, river or lake intakes, rainwater harvest, etc...

- a water treatment plant, which is more or less sophisticated depending on the quality of the raw water

- a distribution system, which is more or less extensive depending on the size of the city and the density of the population (sometimes 1000s of km for a single city) and almost always includes reservoirs or water towers

- pumping stations, which keep the water pipes under pressure to ensure that pollutants cannot enter the system through leaks - better to waste some water than to allow MTBE (for example) to enter through a cracked pipe - and to move water uphill when needed.

- house or building connections, where meters measure the flow of water into households.

- house connections through which sewerage will flow into the collection network

- a collection network, preferably not under pressure to prevent the occurrence of anaerobic conditions and leaks to the environment

- pumping stations to move waste uphill, when necessary

- a wastewater treatment plant to treat the sewerage - more or less sophisticated depending on the nature of the sewerage, the sensitivity of receiving waters, and the regulatory environment

- an outflow pipe, to discharge the treated wastewater into the environment.

Obviously, building, maintaining, and operating these infrastructures is very expensive, and they must be operational 24/7. This is both a matter of convenience and public health. In addition, empty water pipes are subject to infiltration from ground pollutants (see above), and you should never drink tap water in a city where supply is not available on a 24/7 basis. Costs are directly linked to the quality of intake water, the required capacity of infrastructure, the required quality of drinking water (up to or beyond WHO guidelines), the terrain, and the required quality of treated effluent.

In principle, the burden for recovering the cost of investment, maintenance, and operations should be born by consumers, according to how much they consume and how much they pollute (industries pollute water more than toilets, usually). In practice, costs can greatly exceed the population's ability to pay and regulations around the world vary greatly so that this rule is not always applied.

Next post: how much you should pay for water.

No comments:

Post a Comment